New Givelify Features You’ll Love: Interact Quickly with Your Donors AND Enjoy More Security!

You asked, and we delivered. The response to our new Memo Line feature has been outstanding. To make it even better, many of you requested a way to quickly and easily respond to the memos that accompany your donors’ gifts.

Therefore, we’re thrilled to introduce…

Memo Line Dashboard

Beginning today, you will have access to a Memo Line Dashboard in your Givelify account. Not only will you be able to VIEW your donor memos here, but you’ll get to REPLY TO the memos you receive…and from right within the Dashboard!

That’s right: No need to export data or copy and paste email addresses. Simply click on the Memos tab in your Dashboard. Memos that your donors have included with their donations will be listed there.

Acknowledge or reply from within this Dashboard, and the donor will receive an email that includes your response.

How To View and Reply To Memos

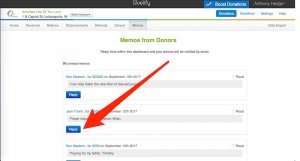

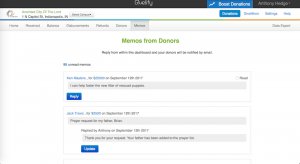

Next to the Donors tab in your dashboard, you will now see a Memos tab. Click that link to view memos. Any donations that include a memo line will be listed including the donor name, the date the donation was received, and a Read/Unread indicator. When you opt to reply to a memo, the donor will receive an email including your response.

Memos will be sorted chronologically, with the newest memos appearing at the top of the list. You can reply more than once to a memo, and an email will be sent to the donor for each response.

Note: donors will not be able reply to your email response. If you are expecting a reply from the donor, please include contact instructions.

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

Settings for Organization Officials

Only officers in your account who have been granted access will be able to view and reply to memos. The account owner will have full access by default. Every official with View or View/Edit access to donations will automatically have the same permissions for memos.

To grant other officials access, log into your Givelify dashboard and follow these instructions:

- Click Settings

- Click Officers

- Click the Permissions button next to the appropriate officer’s name

- Toggle the blue on/off button next to Memos to enable permission

- Using the drop-down box, select Read Only or Read/Write

- Click the blue Update button to save

What Permission Levels Mean

- No Access: that official will not be able to see the memo portal.

- Read Only: that official can view memos but cannot reply.

- Read/Write: that official can read and reply to memos.

More Secure Report Downloading

Next up, we’ve also updated the way you run and access your donation, disbursement, and donor reports. The benefit to you? A more secure way of accessing and managing your donor data.

Previously, reports that took longer than 10 seconds to generate would be emailed to you as an attachment. Some of you expressed a concern that you did not necessarily want that information shared outside of your Dashboard.

Why Did We Make This Change?

Information security and privacy are a top priority at Givelify. So beginning today, you will now receive an email with a secure link to your report.

By keeping your reports within the Givelify Dashboard, we are helping ensure the privacy of your organization’s donor and donation data.

Need Help?

We hope you find these Givelify enhancements useful. If you should have any trouble with either feature, please reach out to our support team.