Givelify Donation Management Dashboard Updates

We appreciate all the feedback you’ve given us about the Givelify donation management dashboard. Your comments, questions and suggestions help us determine the features we need to add or update to make it work for you.

To that end we’ve made some great new improvements to the donation management dashboard.

Givelithon Donor Photos

Givelithons are an excellent way to get people excited about fundraising, and recognize donors in real time.

Now when your members give during a Givelithon their name and profile photo are displayed in a ticker on the left-hand side of the screen.

You can opt to turn this feature on or off using the Settings menu in the donation management dashboard.

Simply move your mouse pointer to the bottom right-hand side of the Givelithon screen and the Settings menu will appear.

Click the Settings button and choose “Hide Donors” or “Show Donors.”

Donation Filtering

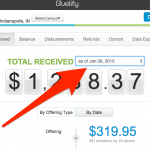

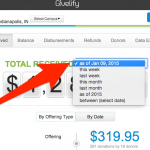

You can now more easily filter how you see donations received. This is a handy way to get a quick snapshot of how your fundraising efforts are performing.

On the Received screen in the Donations section, there is a new dropdown menu beside Total Received. You can view donations received during the current week or month, the previous week or month, year-to-date, or select a custom date range.

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

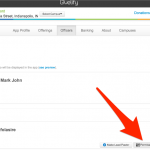

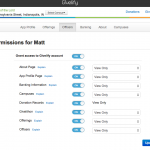

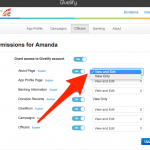

Officer Permissions

Some of your church officers may only need access to certain sections of the donation management dashboard. For example, your bookkeeper may need to access the Banking Information and Donation Records sections, but not have the capability to create new offerings.

Now you can select precisely which sections each officer can access. To update permissions for a particular officer, go to the Officers page and click the Permissions button by that officer. You will see a screen listing each section of the dashboard.

- To completely disable a section for that officer, click the blue toggle button to “Off.”

- When the toggle is “On” you can select “View and Edit” or “View Only.”

These permissions apply only to the officer you have selected.

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

- Click to enlarge

Online Help Center

We have also added an online help center to our Support page. It contains frequently asked questions for donors, churches, and nonprofits.

Having trouble? Check the help center and your question will most likely be answered there.

Other Ideas or Suggestions?

We value the opinions of our member organizations. If you have questions, comments, or other ideas for how to make the donation management dashboard better, please let us know.